For my latest assignment at AIE, I had to, based on the elective I chose, develop an AI simulation where agents either competed or cooperated toward the completion of a goal.

In my case, I decided to create a dogfighting simulator, where AI entities flew spaceships through a 3D space, acquiring targets and engaging them with their gun-based weapons, dodging incoming rounds, and avoiding friendly-fire.

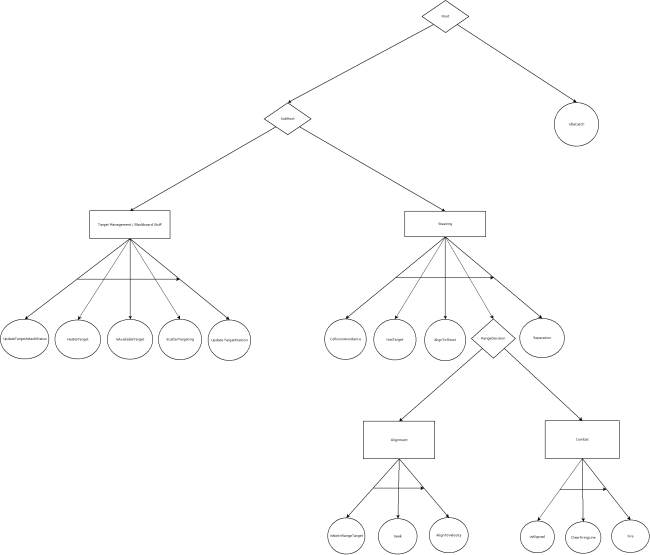

Behaviours

The entities seen in the video operate using a simple Behaviour Tree structure, through which the program traverses, evaluating the nodes in a depth-first, left-right order. In the following diagram, diamonds indicate selector nodes, rectangles sequence nodes, and spheres simple behaviours (either conditions, denoted with an is, has, or are prefix, or actions). More details on the nuances of different behaviour trees are available on http://aigamedev.com.

In this approach, courtesy of Conan Bourke, lead programming teacher at AIE Sydney, sequences begin with the conditions that are required for subsequent actions later in the sequence. This is as opposed to the placement of conditions within the sequence nodes themselves. This method results in nodes that are rather lightweight and flexible – each sequence is just a container of other Behaviour objects through which the Execute method traverses, returning a failure result as soon as one of the children behaviours fails.

The selector nodes will simply traverse each of its branches from left to right, returning a successful result as soon as one of its children reports success. Because a failure will lead to the exiting of the entire branch under evaluation, a selector will, as the name suggests, select a branch or path, and continue down it as long as it remains true.

Both types of composite nodes may contain an unlimited number of children. However, an excessive number of sibling nodes may indicate poor design. In this case, one could try to separate this large grouping into different composite groups, which are then added to the tree in a more elegant manner (as is often the case when using composite nodes), and executed as per the normal behaviour tree process.

In the above diagram, the IdleCatch behaviour will ideally never execute until all enemies are destroyed. This was not always the case, however, as the final behaviour was slightly tweaked – the combat sequence was brought up one level. This meant that the Fire behaviour would execute even when the target was outside the range used to decided whether or not the agent should seek to said target. If this wasn’t done, ships would often end up aligning with their targets but refusing to shoot. As a result, if IsAligned failed, the Steering sequence would fail, and thus the entire SubRoot selector. If IdleCatch wasn’t present, the tree would return a failed traversal, which is an indicator of a malfunctioning and/or poorly designed tree.

If time constraints hadn’t taken their toll, I would have re-factored some of the Steering sequence, as there are some inconsistencies – there are two alignment behaviours that often occur in sequence, meaning the ship would rotate at twice its permitted rate, and the computations contained within would have to be executed twice. This might not seem like much, but when the simulation permits the user to add as many ships as desired, i.e. several hundred, this could well make a difference.

Additionally, if this unrealistic lack of deadline was to exist, a redesign would mean that the IdleCatch behaviour would only execute when all enemies were destroyed. Alas, this was not the case. Regardless, the ships performed as expected, as the potential failure points within the Steering sequence were mostly after any relevant code, and thus nothing of importance was skipped. Still, a design flaw indeed.

Coordination

Inspired by Jeff Orkin‘s presentation – Applying Blackboards to First Person Shooters (PDF download warning) – I wrote a similar blackboard system for inter-agent coordination. Some of the methods include counting records of a particular type, replacing a particular record, or adding a new record. The behaviours in the tree above use this system extensively – the ScatterTargeting behaviour, for example, will count every BB_EnemyID record in its team board, and then the number of BB_Attacking records against each of these IDs, finding the least-targeted ID and writing in a record for itself attacking this particular ship. In this way, the ships on each team spread out in their targeting of enemies, and indicate their selection to their teammates via a BB_Attacking record.

In order to not accidentally engage friendly forces, all entities first execute the ClearFireLine behaviour before actually firing. This performs a Ray->Sphere intersection test between the hypothetically-fired bullet and all friendly ships’ collision spheres within a certain range, and applies a perpendicular force to the ship in question if an intersection is found, so that it may move out from behind said ally. This behaviour alone dramatically decreased the incidences of friendly-fire, even with teams of 50+ ships.

Conclusion

The systems I’ve described above came together to provide dynamic decision making and limited inter-agent coordination in a fast-paced 3D environment. I learned a lot as a result of development, despite its faults, and may well use it as a test-bed in future AI research.